‘Processing Systems: Numbers’ by Sherrill Roland, September 19, 2024 – January 12, 2025. Installation view, Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University.

Brian Quinby.

The truth shall set you free.

Unless you’re Sherrill Roland (b. 1984; Asheville, N.C.). He was charged, tried, convicted, and imprisoned for a crime he didn’t commit.

Accurate statistics for false imprisonment in America don’t exist–can’t exist– but with a total incarcerated population close to 2,000,000, and considering the nation’s history of falsely imprisoning people, a safe estimate for those suffering from that condition would seemingly begin in the thousands.

Roland’s ordeal began in 2012. At the time he was in graduate school studying art at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Out of nowhere, Roland was issued a warrant from Washington D.C. informing him that he had four felony counts against him pending indictment.

“When I went up there for the arraignment, there were two things at play: what I expected it to be you can call it naivety–and then what it really was,” Roland told Forbes.com. “I show up with the understanding that I didn’t do a thing, so therefore, my truth should be all I need. When I got (to D.C.), I go to a (police) precinct to meet a detective, and immediately they were like, ‘Step into this room, remove your belt, remove your shoestrings, place your belongings in this bag.’ Here’s handcuffs, here’s a jail cell. Steel bed. No mattress. Alone.”

He was guilty already.

America brags about the humanity a presumption of innocence its legal system is supposedly based on provides. Ask anyone who’s gone through the system without the benefit of highly paid lawyers and they’ll tell you, the accused start from behind. Sometimes, way behind.

“Then I get taken to a room, get interrogated, and then I go to court,” Roland continued. “I hop in a paddy wagon van and go to Pennsylvania Avenue. I’m shackled from wrist to ankles waiting for my arraignment. This is all before 8:00 AM. Then I have to wait till my name is called and be seen by a judge. At this point, I’m wondering ‘How am I going to court? I have no lawyer.’”

Roland was eventually provided with a court-appointed lawyer, meeting the attorney minutes before seeing the judge. After the arraignment, the lawyer convinced the judge to let Roland return to North Carolina. The court didn’t even know the accused lived outside the District.

What came next feels pulled from a movie.

“They let me go outside of Pennsylvania Avenue. I don’t know how I got there. There were no windows in the van,” Roland remembers. “I have no shoestrings. I have no tie, no belt. I don’t have my cell phone or wallet because all that is in the precinct.”

Chewed up and spit out.

“My court appointed lawyer lent me $20 to catch a cab back to the precinct so I could get my belongings and then I had to catch a flight back to North Carolina that evening,” he said.

Sherrill now realized he would need more than his truth to escape these erroneous charges.

“I surrendered myself with the truth and I was immediately taken advantage of in a way,” he continued. “They took me through the whole gamut without me having any authority over myself and then just left me. Nobody was there to care for me. Nobody cared how I got back to that precinct or gave me instructions (about what to do next). The system got me. I was left going back to North Carolina like, ‘What did I just go through?’”

What he went through was America’s so-called “criminal justice” system, but “criminal punishment” is a better description. The entirety of it, from the cops to the laws to the prosecutors to the judges to the jails, is designed for punishment, not justice.

As disadvantaged as Roland was navigating this system, imagine trying to do so as someone who doesn’t speak English, who’s elderly, who has a physical or mental handicap, someone who’s indigent, someone who simultaneously has children or a sibling or parents to care for.

Roland was an intelligent, healthy young man with a college degree and the support of his family, and this is how he was treated.

Wrongly Convicted

Artist Sherrill Roland.

Photo by J Caldwell / Courtesy Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University

At Roland’s trial, there were no witnesses. No evidence. It was his word against the District’s.

His greatest obstacle, however, proved to be his identity.

“What I (came) to recognize is that the first battle I was contending with, because there was no real evidence to convict, it was my body in that courtroom, and how often does my body–African American male in the District of Columbia–those conviction rates are extremely high,” Roland said.

The court needed a pound of flesh, it didn’t matter whose flesh, and the court got it from Roland, a young, Black, man. Close enough.

“To my naive mind, it’s not like TV. I didn’t have a whole day trial for myself. It was in a bench trial,” Roland said. “I was in a queue. There were people right before me getting their name called and after me. I saw the same judge go through a number of different motions and situations before my name got called, and then when I got called, (the judge) just looked to a detective and was like, ‘In your expert point of view, how often is this case right or wrong?’ And (the detective) was like, ‘We got high numbers.’ And (the judge) was like, ‘That’s all I need to know.’”

Wham bam thank you ma’am.

Roland experienced a bench trial–no jury–the American legal system’s version of a fast-food drive through. Roland doesn’t share the charges he was accused of, but the felonies were reduced to misdemeanors subjecting his case to this adjudication.

In a sadistic irony, because Roland’s trial didn’t include any evidence, there was nothing to appeal after he was found guilty.

Prison Art

‘Processing Systems: Numbers’ by Sherrill Roland, September 19, 2024 – January 12, 2025. Installation view, Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University.

Brian Quinby

On the inside, Roland benefitted from the support of family and friends who continued campaigning for his innocence.

“I had friends and loved ones write me letters and there were other guys that I was housed with who would see that type of participation from the outside world and were like, ‘You might just be alright,’” Roland remembers. “They would tell me stories, the longer the time gets, people get busy. Those letters decrease over time.”

His support network encouraged him to continue making art. He was sent copies of “Art Forum” magazine, the highfalutin international fine art world’s monthly publication.

“It has a type of high art that has no real context inside that specific space I was at,” Roland said of “Art Forum’s” place behind bars.

For artmaking, inmates were allowed access to little golf pencils with no erasers. Roland and his fellow prisoners did the best they could.

“I spent the most time in there were other guys who were drawing out of need,” he said. “They would draw and sell their drawings. I didn’t want to be a competitor. I wanted the least adverse time, so if someone needed something, I would mostly draw out of charity. If your daughter needed a birthday card, I would whip something up for you.”

His perception of art–it’s purpose, value, the making of it–naturally, changed dramatically.

“It made me question why I was even in grad school doing art anyways. That shift of necessity and what art was really used for inside that context of jail just completely flipped my value structure on a lot of things,” Roland said. “It was an overarching, whole Earth turning situation. It’s still those experiences I keep to maintain the integrity of work I make outside of jail about jail.”

Correctional Identification Number

‘Processing Systems: Numbers by Sherrill Roland,’ September 19, 2024 – January 12, 2025. Installation view, Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University.

Brian Quinby

Between 2013 and 2014, Roland served 10 months in state prison, his full sentence. Once released, he was not allowed to leave D.C., serving six months of probation there. Between the pretrial period and his post-conviction probation, he lost control over his life for more than three years.

His case was picked up by Schertler, Onorato, Mead, & Sears, a D.C. law firm. It uncovered facts and details that had been left out of Roland’s trial. With new evidence–actual evidence–presented, Roland received a new trial. Two weeks before that retrial, the other side forfeited the case. The charges Roland’s life were destroyed over were such trash, the attorneys tasked to defend them didn’t even bother showing up to try.

America’s criminal punishment system did its job. Someone was punished. That it was an innocent man didn’t matter. Roland was exonerated in 2015 and his record cleared, but as for the prime years of his life lost, tough nuggets.

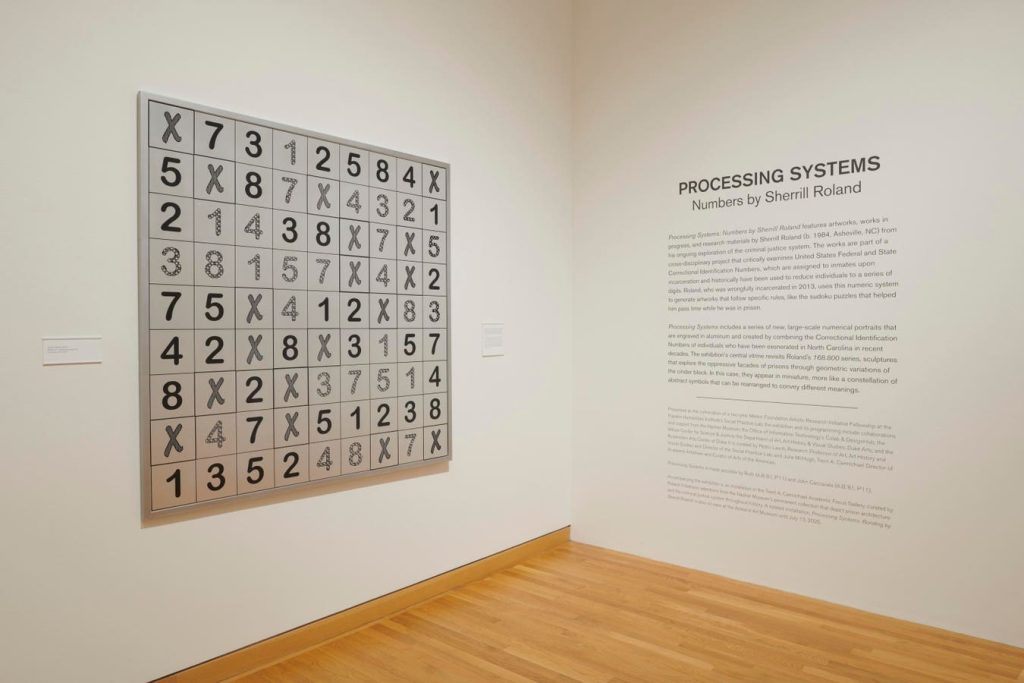

Upon entering the system, inmates are given Federal and State Correctional Identification Numbers. These numbers reduce people to a series of digits. In a new body of work on view at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University in Durham, N.C., Roland has transformed these ID numbers from wrongfully incarcerated individuals in North Carolina into numeric portraits–people as represented by numbers. Roland researched the cases of other wrongfully convicted individuals through conversations at Duke’s Wilson Center for Science and Justice. The project and exhibition were produced as a Mellon supported FHI Social Practice Lab Fellowship.

Refuting the dehumanizing and anonymizing aspects of this system, Roland uses these digits to generate number-based artworks that follow specific rules, like sudoku puzzles.

“I do my best to forget it,” Roland said of his ID number.

He remembers. His family members do too.

On the inside, you’re not Sherrill Roland. When family and friends inquire about a visit or your case, they don’t ask for or about Sherrill Roland. They refer to your number.

We’re all 1s and 0s in a digital age, but these identification numbers are something else. Analog. A throwback. These numbers don’t digitize for fast sorting by computers, they dehumanize for slow sorting by people. Sorting of people. They’re designed to reduce. To warehouse.

They’re designed by a criminal punishment system with a similar mission of dehumanizing, reducing, warehousing.

“My intention is to show the softness of the human being, to get a warmth out of the human being–there’s a human being attached to this (number)–but then also trying to highlight the coldness and harshness of the system,” Roland explained. “I’ve had people interact with this work and ask me, ‘I want to know about this person.’ I’m glad people feel that way. I’m glad they have a response to make them want to care for the person because you are reacting to the coldness of a system reducing a human being in this work.”

Sometimes Roland reveals the individual represented by the scrambled numbers, sometimes not. The titles of works include the number of days that each person was wrongfully imprisoned.

“Processing Systems” will be on view at the Nasher Museum through January 12, 2025.

On view concurrently is a complementary installation curated by Roland featuring selections from the Nasher Museum’s permanent collection depicting prison architecture and the criminal justice system throughout history.

A related installation, Processing Systems: Bonding by Sherrill Roland, is on view at the Ackland Art Museum at UNC-Chapel Hill until July 13, 2025.

Source: https://www.forbes.com/

More Stories

NFL Picks, Props And Odds For Week 13 Prime Time Games 49ers-Bills And Browns-Broncos

The World’s Best Whiskey—According To The Authors Of Bourbon Lore

Of Toys And Tokens – In Conversation With India’s Top NFT Artist