For more than half a decade after World War II, Soviet spies beamed powerful radio waves at the United States embassy in Moscow. The energy penetrated the beak of an American eagle carved into a Great Seal hanging in the ambassador’s office, powering a hidden microphone and transmitter. Presented to the ambassador by Stalin’s Young Pioneers, the carving was a typical diplomatic gift of the era. The apparatus it concealed, in contrast, was so futuristic that it took the combined efforts of the FBI, CIA, and MI5 just to figure out how it worked.

The Thing (as the bug was dubbed) became an icon of the Cold War when the US presented it in a 1960 United Nations Security Council meeting, seeking to deflect international censure after the Soviets shot down an American spy plane and captured the pilot. The ingenuity of the listening device was self-evident. But nobody imagined that the inventor was one of the 20th century’s most famous musical innovators. The Thing was invented by Leon Theremin, whose previous investigations of radio waves resulted in his namesake musical instrument.

A new exhibition at the Wende Museum, Counter/Surveillance, explores connections between surveillance and the arts, and their shared focus on observation. Although few crossovers are as direct as Theremin’s, the convergence of art and technology is a common theme, as is the attention to affordances – the ability to notice how techniques might be applied for alternative purposes – as much as the talent for reconnaissance.

Kolodzei Art Foundation

One of the most foundational crossovers, long predating radio monitoring, was the study of anthropometry. From classical Greece to the Renaissance, artists have shown a longstanding interest in measuring the human body to determine ideal proportions in sculpture and painting. Anthropometry led to rules such as those seen in Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. These rules encoded a standard of beauty.

In the 19th century, anthropometry was taken up by criminologists. Seeking to track repeat offenders in Paris, the French police officer Alfonse Bertillon supplemented mug shots with systematic measurement of features such as the breadth of the head and the length of the left foot. Of course, Bertillon was attempting to achieve the opposite of Renaissance painters, looking for distinguishing variations between people instead of seeking an eye-pleasing average.

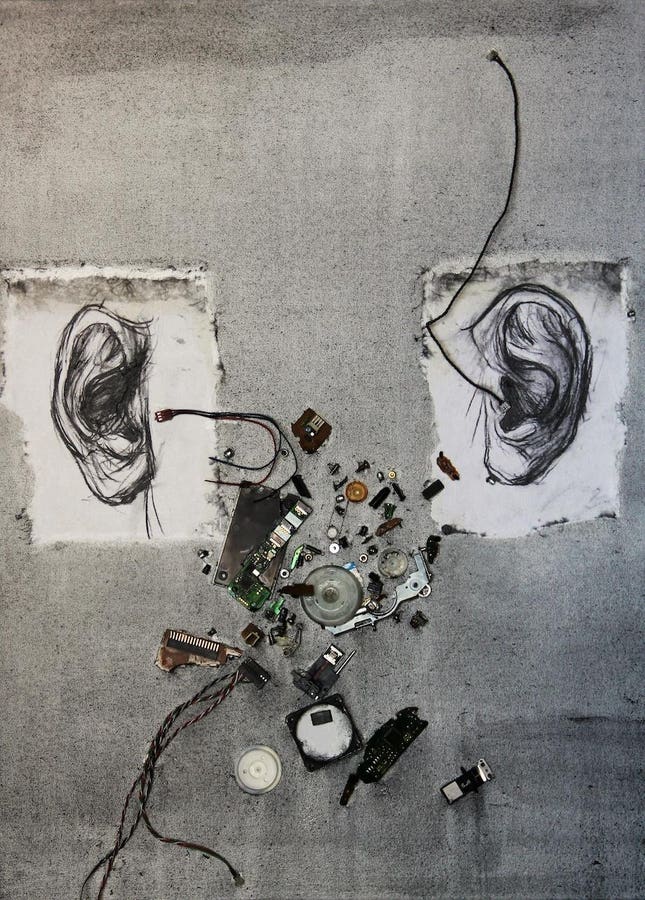

Bertillonage, as his practice came to be known, provided law enforcement with an extraordinarily effective index for monitoring and identifying people. Even after the measurements were supplanted by fingerprinting, anthropometry was an important part of criminology and surveillance. With enough training, police and spies learned to see through disguises by noticing subtle variations in faces such as the shape of an ear or the distance between eyes, no calipers needed. Manuals distributed by the CIA and Stasi – some of which are on view at the Wende – could easily supplement a life drawing curriculum. As artists were increasingly shifting their attention from generalities to specifics, Bertillon’s heirs were learning to see like artists.

Ironically, artists were often the subject of governmental observation. During the Cold War, restrictions on free expression made many artists into dissidents. Artists were able to observe political conditions all too well, and to convey what they observed in ways that could upset power relations both within and across rival nations.

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the reunification of Germany revealed the extent of monitoring behind the Iron Curtain. The sheer volume of material astonished even those familiar with state paranoia. But it’s taken artists to reveal the underlying madness. They’ve done so by observing the observers.

Wende Museum

One of the most beguiling artworks in the Wende exhibition was created by Verena Kyselka, an underground artist from East Germany who gained access to her Stasi file in 1993. Struck by the discrepancies between the official record and her memories, Kyselka made Stasi the reports into elements of an autobiographical collage. “What is written in these files mainly concerns banalities,” she explains in a text accompanying the piece. “[T]hrough the initial, orally received interpretation of the informant, and the written-interpretation of the Stasi officer, [banalities] become subversively active.”

For all their penetrating surveillance, Kyselka’s observers were oblivious to the meaning of what they were monitoring. Although their misrepresentations might have been intentional, suspicions were so systematic that verisimilitude was probably impossible. Quashing the independent vision of artists, a society loses track of reality.

Growing up in China, Xu Bing understands this problem as well as any artist alive, and has confronted it more effectively than most. His contribution to the Wende exhibition stands out as a sweeping portrait of a surveillance state and the paradoxically equivocal picture that arises when hundreds of millions of video cameras are monitoring everything that happens in public.

Dragonfly Eyes is a feature length film cut entirely from publicly accessible surveillance footage. The story is made up: A woman raised in a Buddhist temple leaves to find her way in the big city. With this fictional narrative, Xu suggests that others could be created in the same way. The potential for confabulation is infinite.

Through the appropriation of CCTV footage or a Stasi file, artists bear witness to conditions intended to constrain them. Perhaps even more subversively, they transform skullduggery into art. A bug becomes a theremin.

Source: https://www.forbes.com/

More Stories

Denmark’s Medical Cannabis Trial Program Set To Become Permanent

10 Best Ski And Snowboard Resorts To Use Your Epic Pass This Winter

A 5.72-Carat Fancy Intense Blue Diamond Could Fetch $8 Million